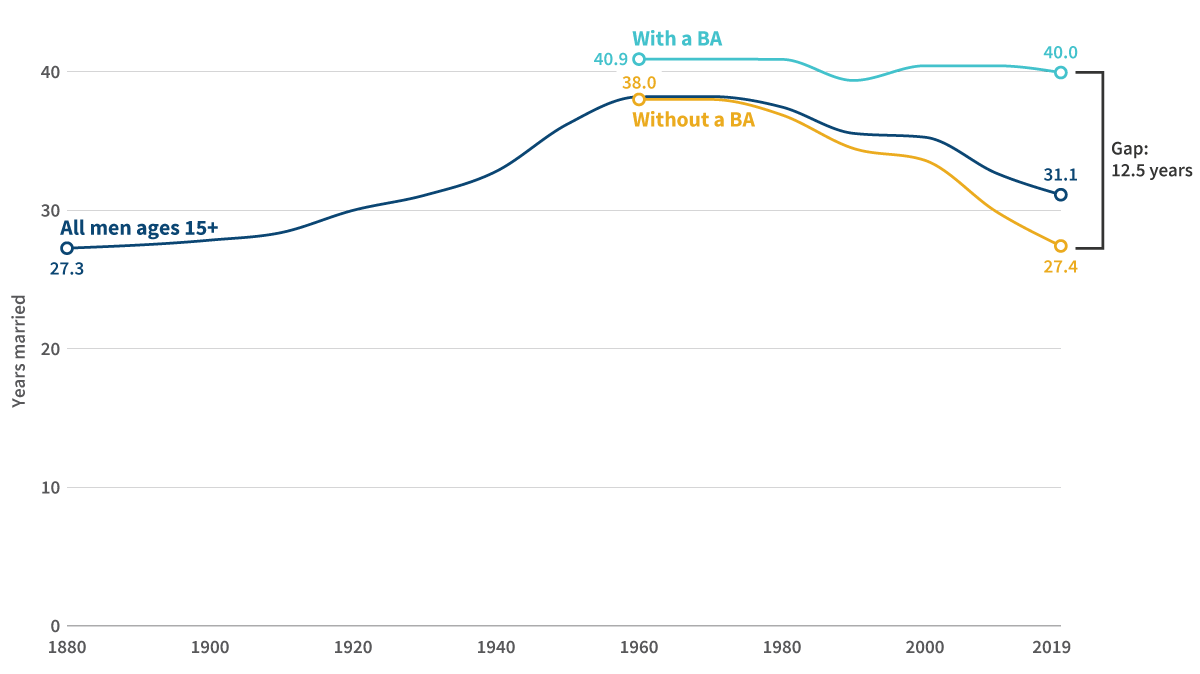

New research shows that the number of years men spend married has dropped sharply—especially among those without a bachelor’s degree.1 In 2019, men without bachelor’s degrees could expect to spend 27.4 years of their lives married—the lowest level since 1880 and down from 38.0 years in 1960 (see figure).

Yet for men with bachelor’s degrees, the expected number of years married has stayed about the same for the past 60 years, slipping by less than one year (from 40.9 years to 40.0 years) between 1960 and 2019. Study author Christine R. Schwartz and colleagues at the University of Wisconsin-Madison used census data on marital status from the University of Minnesota’s IPUMS database and calculated life expectancy based on data from the Human Mortality Database and other sources.

Their research reveals a growing marriage gap tied to education: In 2019, men without a bachelor’s degree could expect to spend 12.5 fewer years of their lives married than men with a bachelor’s degree. The researchers say this is the first analysis that “combines estimates of the widening gulf in adult life expectancy by education with changes in marriage to estimate divergence in expected lifetime years married.”

Figure. Men With a Bachelor’s Degree Spend More Years Married Than Men Without One, and the Gap Is Growing

Men’s lifetime years married (as expected at age 15), 1880–2019

Note: Only a small share of men received a college degree in 1960 and before, so lifetime years married for all men and those without bachelor’s degrees were likely very similar for those years.

Source: Christine R. Schwartz, Rodrigo González-Velastín, Anita Li, “Lifetime Years Married Held Steady for Men with a BA Degree Since 1960 but Dropped to Lowest Level Since 1880 for Men Without a BA,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 120, no. 28 (2023): e2301983120.

The results for women were similar to those for men, but in 2019, women with bachelor’s degrees were expected to spend fewer years married (35 years) than men with bachelor’s degrees (40 years).

Diverging Family Patterns and Deaths of Despair Contribute to a Growing Marriage Gap

Schwartz and team link the growing marriage gap between men with and without degrees to two key trends: diverging family patterns and a widening gulf in life expectancy for people with different levels of education. Trends in life expectancy can either extend or shorten the number of years men and women spend married; in 1880, marriages were more likely to end by death than divorce.

“Deaths of despair,” often defined as suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related deaths, have disproportionately affected men with less education, Schwartz noted. Men without college degrees have also faced a higher risk of death from heart disease and cancer, contributing to the widening gap in mortality, she reported.

In 1960, the gap in life expectancy for Americans ages 15 and older was just three years between those with a bachelor’s degree and those without (57 years and 54 years respectively), the study found. But life expectancy started to drop among men without a bachelor’s degree in 2012, and by 2019, the life expectancy gap had grown to eight years.

The share of men who are married has also dropped sharply in recent decades, especially for those without college degrees. While 71% of men were married in 1970, by 2019, only 49% were, as people married later, lived together more, and divorced or separated more often. This decline was much more pronounced for men without bachelor’s degrees; between 1960 and 2019, their marriage rate dropped by 24 percentage points (from 70.5% to 47%), while men with bachelor’s degrees saw a 15 percentage-point drop ((from 74% to 59%).

Why does it matter if people are spending less of their lives married? Research links marriage to a host of positive outcomes in health and well-being (especially for men), including better physical and mental health, longer life expectancy, lower alcohol use and drug use, and a lower likelihood of committing crime. But these relationships may not be causal, according to Schwartz, who notes that research is ongoing.

The growing education gap in marriage is also a symptom of increasing economic inequality, Schwartz noted.

“The declining economic fortunes of less educated men have made it increasingly difficult to achieve the economic security many people desire to have in marriage,” Schwartz said.

If current marriage patterns continue, the researchers note, we can expect that people will spend even less of their lives married in the future.